Assemble

Blood in the machine

Exposition

Sandbox Exhibition #2 1

History explained why now existed, how yesterday became now 2

30 years ago, in 1994, Le 19, a regional centre for contemporary art named after its location at 19, avenue des alliés in Montbéliard, was born. The following year, it moved into a building whose plot had been acquired in 1921 by the Peugeot company to open its first repair workshop. This early 20th- century industrial building was sold to the City of Montbéliard in 2009, and is now one of the city outstanding industrial heritage architectures. Its metal framework and glass roof with no intermediate supports give it a special cachet and are a source of inspiration for the artists who are invited to work there. This is the case for the British collective Assemble, whose “Blood in the Machine” exhibition 3, draws on the stories that run through the place.

Assemble is a multidisciplinary collective working in the fields of architecture, design and the visual arts. Founded in 2010 to design a single project (The Cineroleum, the temporary occupation of a former service station in London by a cinema), Assemble has since delivered a diverse body of work recognised by international awards (including the Turner Prize in 2015 in the United Kingdom for The Granby Workshop in Liverpool). They promote a democratic and cooperative working method that enables the production of artistic projects that are co -constructed and socially engaged by nature, and always based on the exploration of a place, a territory or a situation investigated “from the inside”. Their projects combine all the scales of construction to generate “learning by doing” situations.

In contrast to traditional architectural practice, which is generally based on the principles of commissioning (without consulting future residents or users of the site), they are interested in situations where it is possible to call into question the way in which budgets and legal frameworks are managed. As “ignorant architects 4 ». Assemble are attempting to push back the boundaries of their disciplinary language and incorporating other forms of teaching, based on trust and collective intelligence. The collective draws on “new fields of intervention that in one way or another link architecture to places, to relationships between people and to the challenges of our time […] the social fabric, urban policy, curative practices, […] literature and other fields of action that describe the complexity of the environments in which we live, in order to discover new ways of living 5 ».

[…]

As part of Blood in the Machine, the collective is drawing on the history of the art centre’s building, aiming to (re)transform it into a space examining the role of production and technology in the social, cultural and economic life of the town and wider society. A long preliminary process consists of investigating local resources and technologies conducive to amenity 6 in this situation.

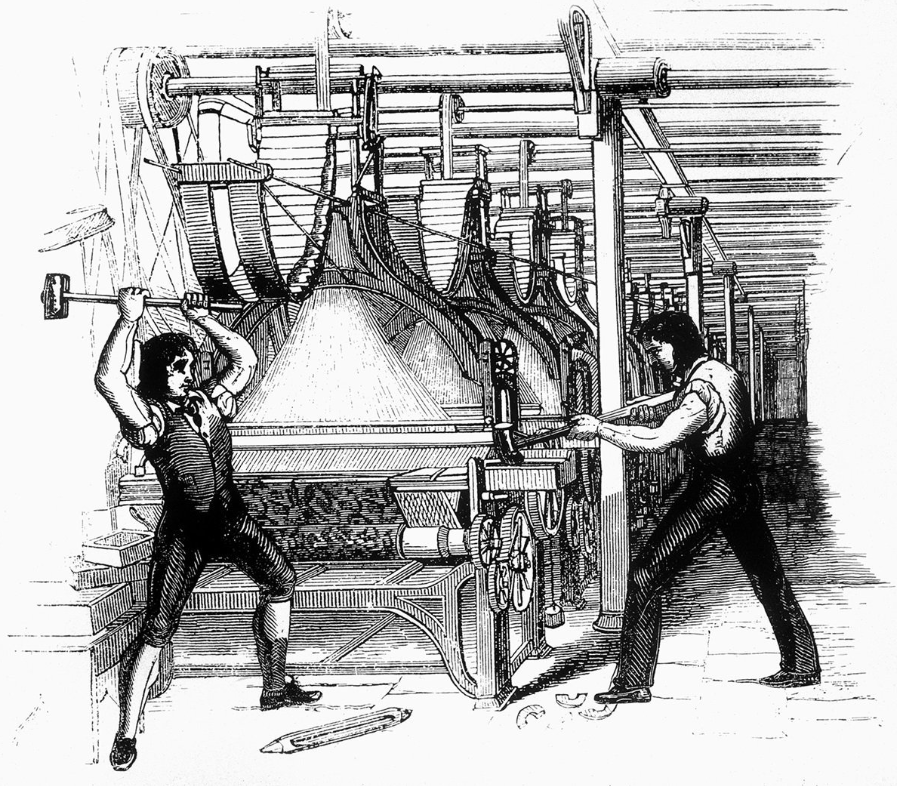

Through surveys, mapping and the collection of spoken word, Assemble is uncovering the many layers that make up the bioregion. 7 Although the industrialisation of the Pays de Montbéliard was encouraged by the presence of water, wood and iron ore, the most recent studies suggest that its exceptional development was mainly determined by the geographical environment, which was not enough fertile for an extensive agriculture, the political, cultural and religious history of a Protestant enclave in France 8, and a general dynamic of progress. In addition to the famous local creations in ironworking, such as bicycles and automobiles, the Montbéliard region has developed recognised expertise in watchmaking and textiles. Verquelure, known as “verquelée” in the region since the Middle Ages, is hand-spun from hemp grown on damp plots close to dwellings using a typical Montbéliard spinning wheel, and has also contributed to the development of the region’s textile industry. Spinning mills developed around 1810, with machines imported from England by Charles-Christophe and Jean Jacques Peugeot. This history suggested to the artists an ethical starting point, that of the historic British Luddite movement 9 which provides the philosophical thread for the project. Assemble takes up the observation that “throughout history, at least in the Western world, the project of technology has been to capture the skills of the craftsman or artisan, and to reconfigure their practice as the application of rational principles, the specification of a has no regard for human experience and sensibility 10 ».

Through the “medium of exhibition”, they are attempting to measure how this sensitivity, these affects and moods, could be reintegrated into a reflection on the technologies of tomorrow in the region. So, while Blood in the Machine brings together archival material and local heritage objects from the collective’s research, it is also intended to have other effects than just an exhibition. It offers a central space for dialogue within the art centre through which “the space will play a dual role as a material and social infrastructure, helping to integrate the project into the community”. By exploring “while doing” materials and resources, local self-build initiatives 11 and architectural heritage in search of new uses, the collective is proposing a new way of looking at them, with the aim of prompting a fundamentally anthropological questioning of what constitutes the sources of our imaginations and our activities. Assemble is taking advantage of the exhibition format to assert “a radically different approach, one that can offer not only a diversity of objects but also contextualise a social field in which and from which the objects are produced and draw their meaning 12 » in order to allow, in this particular case, ways of thinking critically and imaginatively about the future of the town and the wider territory.

Blood in the Machine hopes to imagine potential narratives for the future, and to explore new uses for local resources and the development of a bioregional economy. It is conceived as a collective process of experimentation to help shape a constructive and positive vision of the future, one in which our relationship with technology is empowering rather than privative.

The avant-garde is not a material innovation, it is not technological art or anything else. It’s a way of behaving, a way of confronting things, human beings, and substance; it’s an attitude defined before the world. It is a permanent transformation 13.

Adeline Lépine, Curator of the exhibition

- Since 2023, 19, Crac has been offering visitors the chance to explore its potential as a public space during the summer months. The exhibitions during this period are conceived partly as a playground for artists and audiences, presenting « sandbox » works to be activated. The term evokes both a children sandbox and a type of video game. The first of these, La Ville en Jeux (The City at Play), was commissioned in 2023 from The Outsiders, a collective based in Utrecht, Netherlands. ↺

- Élisabeth Vonarburg, translated from the French version of her book (1992) entitled first In the Mothers Land and later republished in English as The Maerlande Chronicles. ↺

- The title is taken from a book by Brian Merchant, a journalist specialised in new technologies. Blood in the Machine: The origins of the Rebellion again Big Tech was published in September 2023 by Little, Brown and Company. It is an essay that questions and notes the effects of the automation that has continuously transformed our world, by crossing the history of the Luddites (see note below) and our contemporary times. ↺

- Expression taken from the article “Alchemy of the classroom” by Ethel Baraona Pohl & César Reyes Nájera in Volume #3, Learning, Archis, 2015. Teachers at DPR Barcelona, they refer to the experience of Joseph Jacotot (1770-1840), a French pedagogue and teacher who created a method of “intellectual emancipation” that demystified the authority of the teacher as the person who “knows” and passes on knowledge to students who are supposedly “ignorant”. Jacotot’s research is the subject of Jacques Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster, published in French in 1987 by Éditions Fayard. ↺

- Ethel Baraona Pohl & César Reyes Nájera. Op. Cit. ↺

- Environmental amenity refers to any aspect of the environment that is appreciable and pleasant within a specific place or site. It also implies that its sources are already present or easily accessible. It is therefore based on close observation of the local context and making the most of its immediate resources. ↺

- “Literally and etymologically speaking, a bioregion is a “life-place” - a unique region that can be defined by natural (rather than political) boundaries, and which possesses a set of geographical, climatic, hydrological and ecological characteristics capable of hosting unique human and non-human living communities. (…) Most importantly, the bioregion is the most logical place and scale for a community to take root and become sustainable and life-giving. R. Thayer, LifePlace. Bioregional Thought and Practice, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023, page 3. Extract translated into French in Mathias Rollot, “Aux origines de la “bioregion”. From American bioregionalists to Italian territorialists”, Métropolitiques, 22 October 2018. URL: https: //metropolitiques.eu/Aux-origines-de-la-bioregion.html ↺

- The Montbéliard region was a Principality owned by the Counts of Württemberg from 1407 to 1793, and as such was part of the Holy Roman Empire, although it was entirely French-speaking. ↺

-

Luddism was an English workers’ revolt at the dawn of industrialisation (1811-1816), which particularly concerned workers in spinning mills following the introduction of new machines that encouraged the automation of a number of production processes and the elimination of jobs within industries. The movement was repopularised in the 1980s in the United Kingdom during the workers’ revolts. It is once again very much in the social and political news as part of the resistance movements against the massive introduction of new technologies into our daily lives. The movement has been popular since the 19th century, with some artists taking a stand in favour of the Luddites. One of the best-known examples is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus, published in 1818, which can be read as a metaphor for the class struggle between the bourgeoisie (Frankenstein) and the workers (the new form of life created by Frankenstein).

« When they smashed machines, workers in the Midlands were primarily protesting against « shoddy work » and « cheap labour » that undermined the honour of the trade. As the Nottingham Review, a radical middle-class newspaper, wrote in 1811: « machines, or trades (…) are not destroyed out of hostility to all innovation (…) but because they enable the manufacture of goods of little value, of deceptive appearance, which damage the reputation of the profession and which, in this way, contain the seeds of its destruction ».

Vincent Bourdeau, François Jarrige, Julien Vincent, “Les Luddites – bris de machines, économie politique et histoire”, Editions ère, Clamecy, 2006. ↺ - Tim Ingold, in Being Alive: Essays on Movement, “Knowledge and Description – chapter 4 Walking the Plank meditations on a process of skill”, Routledge, London, 2011 ↺

- More specifically, the “Maisons-Castors”, built by workers in Audincourt through self-construction and self-determination by sharing knowledge between 1951 and 1956. ↺

- Yvonne Rainer in her preface to DEMOCRACY - a project by Group Material, edited by Brian Wallis for the Dia Art Foundation, “Discussion in Contemporary Culture” series, Number 5, Bay Press, Seattle, 1990. In it, the artist discusses the effects of Group Material’s and Martha Rosler’s exhibitions at the Dia Art Foundation between 1988 and 1989, which, in her view, brought together a new format of non-alienated exhibitions in which “the value of art as a social force” was affirmed. ↺

- Federico Morais, « Federico Morais, critico e criador » on the Arte Brasileira website, as at 8 December 2012. ↺

Infos utiles

The exhibition Blood in the Machine is supported by the Fluxus Art Projects and is stamped Pays d’Agglomération de Montbéliard French Capital of Culture 2024.

It involves collaboration with the Municipal Archives of the City of Montbéliard, the Museums of the City of Montbéliard, the Musée de la Paysannerie in Valentigney, the Pays d’Agglomération de Montbéliard Tourist Office, the heritage department of the Pays d’Agglomération de Montbéliard, the Société d’Émulation de Montbéliard, L’Entreprise Métis’ in Etupes, the Conseil de Développement de Pays d’Agglomération de Montbéliard, the Medvedkine group in Sochaux and the ISKRA production company.

The artists would particularly like to thank Jean Cadet, Pierre Lamard, Mathilde Chénin, l’atelier Paysan and the town of Exincourt.

Website of the collective Assemble

Download the exhibition press release

Blood in the Machine, Jeremy Waterfield